It’s been a thrilling albeit sometimes rough ride this term. I’ve learned a ton. The local group I’m privileged to be part of has gelled far beyond my expectations, and activity across the network has often been a wonder to behold, even in these early days and with sometimes very difficult situations emerging. But the seminar is a work in progress, of course, and there’s lots to tweak and think about. I’ve been in conversation with several folks about the tweaking and thinking, and one particular exchange was so rich that I thought I’d adapt it for a blog post. The result is largely from that one exchange, but with many things folded in from other conversations. I hope I haven’t misrepresented the exchanges in any way, or merely erected straw men to knock over. As always, I welcome and invite comments, if they’re civil. I won’t identify any of my conversational partners in what follows, as I haven’t asked permission to do so. But these are questions and ideas that did spring from real conversations–I’m not just making up interlocuters here.

I hope some of what follows is helpful or stimulating or both. It’s certainly long–no doubt, too long–but I thought the topic worth exploring at length. So here we go.

What’s the larger purpose of the seminar, and how can we get there? How much prescriptive and explicit “set-up” is necessary? How much open-ended “explore and invent” is possible when the readings are so complex?

I certainly want, as one colleague recently put it, to remove the fear barriers, open the doors, and create a runway for creativity. The question is how to do that. I’ve thought about that a lot, and for better or worse I have definite ideas. J For me, the key (as with all the work I do as a learner and teacher) is to work intensively with complex ideas that resonate both personally and socially (by which I also mean “culturally”). The ideas can be quite varied, and they can be expressed in different ways, but without them, there’s none of the deep synaptic work that in my view is necessary for genuine freedom and a new or renewed imagination. Then the question is how best to engage with ideas, especially when they’re complex. I feel very strongly that trust and conversation among spirited companions is the best way to engage with those ideas, especially when they’re new and complex and perhaps even off-putting, because in the end, trust among fellow learners opens the path to the next level. Or so I believe. I do also believe that guidance is necessary, however, and with several colleagues I’m now thinking about what form that guidance might take, and to what extent there should be explicit guidance.

Is the seminar merely flogging folks with hard technical readings the way we’ve flogged them in the past with technologies they don’t understand but are forced to adopt (e.g., “we will all now migrate to version x.x of software y—and no complaining!”)? Shouldn’t we find seductive ways to open minds and free imaginations instead of offering more impenetrable, painful experiences? Isn’t seduction (e.g., an iPad) better than flogging (e.g., requiring hard reading)?

Well, I hope flogging and seduction are not the only alternatives! I firmly believe in catching my flies with honey—that’s why God made honey-pots—but I want to suggest a third option: not flogging (bad extrinsic motivation—“the beatings will continue until morale improves,” and that sort of thing) or seduction (good extrinsic motivation that activates all the pleasure centers—hey, I enjoy that as much as anyone, believe me) but encouragement. Giving heart. Flogging suggests harsh paternalism and inspires resentment. There’s also a perverse pleasure in being flogged, as it allows one to escape any personal responsibility and blame it all (whatever “it” may be) on the Man, or the Woman, or the System, etc. Seduction sounds great by comparison, but it also evades the question of personal agency and plays into a “now, isn’t that *easy*?” paradigm that can be just as crippling as the leg-breaking. Not everything will be easy, not everything will be seductive, not everything presents itself immediately as fun. Some things are bound to seem or be strange or off-putting at first.

Take the universal experience of culture shock, for example. Yes, Steve Martin was right: they really *do* have a different word for everything in France. So what to do? Learning the language out of a phrase book is not fluency, but narrowly conceived utility. Learning the language with drill-and-kill memorization is similarly limiting. If all one wants to do is ask for directions, the first way will probably work as long as the directions are simple and straightforward. For real human complexity, though, it isn’t enough. The second way is also problematic, as Milton himself noted. (There’s my Milton reference for the day.) If all one wants to do is master the language in a limited way that does not engage with the real beauty of the language’s expressive capacity until very late in the game, by that time the student may simply have given up, or the capacity for real pleasure may be gone. I believe there is an encouraging way to do the hard work that does not take the big-picture expressive pleasure out of the experience even as there is unavoidably a steep learning curve—at least if one wants real fluency and an unfettered imagination.

But all of that brings into sharp focus the question of why one would want to “learn French” in the first place.Or to put it another way, why should we work hard to move our minds into bigger, messier, less certain, and less immediately comprehensible frameworks? For me, this whole New Media thing is that question, written larger and more comprehensively than anything before in human history. Ted Nelson says we can and must learn computers NOW. He wrote that in 1974. His essay makes it clear, I think, that it’s about expanding human capacity, augmenting intellect. His idea of “fantics” is wildly seductive to me, sure, but not because of ease of use. I don’t know if I’m explaining myself all that well. I guess I’m trying to say that the question of “what does it mean to learn computers?” is far larger and more urgent and more important than either the “flogging” or “seduction” can address. That said, I certainly think we can make the seminar more seductive through many means, cultural as well as technological (if there’s a real difference there, that is).

But aren’t these readings in The New Media Reader just stuff for techies? Can we really expect folks from traditional disciplines to work to understand them? What if people are just so turned off that they never come back? Don’t we risk simply making everyone defensive because they feel flogged by materials they don’t understand and don’t care about?

First, I’d want to challenge the assumptions implied in this question: that these essays are all “for techies,” that they’re all dry and difficult, and that people from traditional disciplines won’t find connections in there. My experience with the Baylor groups has been that some essays are more immediately accessible than others, but that there are connections in there for every discipline, for every role, for every learner, and that in finding and exploring those connections together (via those “nuggets” I always talk about, those points of resonance, puzzlement, or resistance) we become a true learning community. I really don’t think the situation is as dire as the question implies. This semester in particular, I’m seeing a truly astonishing blossoming of ideas and fellowship not only in the Baylor seminar but across the entire network. There are huge exceptions of course, but I never went into this thinking that the goal was a 100% yield. I’ve never been in a learning situation where that was the case, anyway. My goal is not to hit 100%, but to scale the experience (via the network, and over time) so that a critical mass of digitally awakened imaginations can begin to collaborate on the hard work of building, reforming, and augmenting education in the 21st century.

Perhaps some people do feel a bit bruised by some of the readings. It makes me unhappy to think so, but I’m sure some do. Well, here’s the deal, for me. If they feel flogged, how can we as fellow learners and, sometimes, guides help them not feel flogged? There’s a stark difference between being required to upgrade to Windows 7 or to lock one’s courses into Blackboard 8 or 9 or 15 or whatever and being encouraged to engage with ideas that are complex and suggestive enough to furnish mental models that truly liberate the digital imagination. The question for me, then, is how to encourage people to engage carefully, openly, bravely, and joyously with new readings that are not necessarily in their “first” language, in terms of discipline or preference. But we know how to do that! We are teachers, after all, and we can do that for each other. The idea I have is that smart and curious folks working together can in fact equip themselves with a core set of ideas and conceptual frameworks that will empower them to think clearly, bravely, and innovatively about networked computing, the force that has enabled the largest increase in expressive capacity in the history of the human race.

Also, I don’t believe we will ever be able to craft any experience in which folks are not put off by something. If they feel they’re simply incapable of understanding the essays, in my view the problem is the feeling, not the reality. I firmly believe we *are* capable of understanding the essays. And I firmly believe that these ideas and conceptual frameworks are the ones we really should engage with—and that these essays (with some tweaking, sure; no syllabus is perfect or final) are the motherlode, the resonance frequency.

OK, but are we being innovative enough? Isn’t this just a 1930s-style graduate seminar that’s just enhanced somewhat by network technologies?

As my friends the edupunks know, I am not anti-tradition by any means. This experience is in fact, and unapologetically, modeled on a graduate seminar—but a graduate seminar in which there are no grades, no “deliverables,” just the responsibility and privilege of engaging with fellow learners, locally and remotely, in conversation about deep, rich, complex, and urgent ideas. And I do think that a face-to-face meeting at the local level is crucial to the success we want. So I really don’t think there’s anything wrong—and in fact I think there’s a lot right—because we’re doing something that’s based on a structure from earlier times (I’d say, at least since Socrates, or the Peripatetics). I also don’t see the seminar as being “just enhanced somewhat” by the ICT we use. I don’t see this as a small thing, a “just” thing. The networked design, the blogging, the Deliciousing, the tweeting, the forum (all of which is being used, to varying degrees, across the network) builds a platform and makes the intellectual activity visible. What folks build on that platform and how they respond to and contribute to that activity is up to them. That’s the beauty of it, and the challenge of it. I do agree, though, that I and we can do a better job of articulating the platform and explaining what the seminar can be, why the readings are there, what the experience may be like (including the side-effects, for some, of nausea and heartburn until we’ve gotten a few weeks in :).) My impulse is not to impose my own thoughts too strongly on the platform but to let folks discover it as they go, and invent new pieces that we can all learn from. This puts a huge burden on the individual group leaders (or facilitators, if you prefer). We need to be in conversation more ourselves. I see that very clearly now. I’ve got some ideas in that regard. And I think all the seminarians, myself included, can and should work harder to encourage each other to blog, comment, and comment on other people’s blogs at other sites. It’s a lot to try to do in twelve weeks, but it’s worth doing.

But aren’t we still stuck in tech 101 by sitting in chairs and using printed books? Shouldn’t we be thinking about radically reshaped learning experiences?

I don’t agree with the assumptions underlying the question. Sitting at tables and discussing printed material is not just primitive, we-can’t-do-better, and unimaginative. It’s the core of building a local cohort dedicated to imagination and innovation. I don’t think the Internet makes the idea of local communities obsolete by any means. Rather it augments the local with the global—and vice-versa. Again, I don’t see the networked part as “just enhancing” something. I think the networked part makes the richly effective traditional face-to-face engagement into something that goes all the way to 11—something huge. I think that in fact it DOES radically reshape the learning experience. I think the radical nature is what’s putting people off, frankly. Cool tools ain’t radical. Getting early adopters or even long-time resisters together to geek out on seductive stuff isn’t radical. Workshops aren’t radical. Many times, even “course redesign” isn’t radical. What *is* radical is the idea of a seminar, unfettered by grades or projects or deliverables, networked so that the intellectual activity is visible and richly interactive. More on this below.

But isn’t blogging just another form of professional writing, one that strongly resembles the writing for professional journals we’re already used to?

Oh no! I’m actually dismayed to think anyone would think so. I think blogging is utterly (and radically) unlike writing for professional journals. Maybe part of the problem here is that folks don’t have a deeper understanding of blogging itself. It’s freer, looser, more voice-filled, more exploratory, more goofy, more fun, more multimodal. I’ve written for a number of professional journals, and blogging isn’t that at all—and shouldn’t be in this context either. It should be thoughts, scraps, false starts, stories of the progress of one’s own learning and missteps and questions and problem-finding…. The local seminar leader/facilitators should make these distinctions clear, I think—but that’s hard, I understand, unless one has some experience with blogging. Again, there is a certain amount of bootstrapping oneself into understanding that’s simply unavoidable (but can be fun, too).

I think the fact that blogging is utterly unlike writing for professional journals is one of the reasons it’s so hard for faculty to do (or at least to start doing). They feel lost and vulnerable without those professional journal structures. And they’ll say weird things to me like “who wants to read what *I* have to say?” This from people who are professors making their living from people who pay to hear what they have to say! No, I truly believe that blogging in this context should free us for authentic learning and sharing of our learning. I’m seeing that happen in the Baylor seminar, big time, partly through luck of the draw, partly through experience (I have the good fortune of being on my *second* iteration locally, and fifth in terms of the undergrad class, so I’ve got more mistakes of my own to learn from), and partly because of another part of the “networking” I kind of backed into this time: teaching the first-year seminar at the same time as the faculty-staff seminar. *That*’s been extremely interesting and suggests models of education that are well worth exploring in more detail, particularly as the two groups begin to interact. This too could scale in interesting ways.

But we’re still conscious of our audiences, just the way we are when we write for professional journals. The only thing that’s really different here is the speed of publishing and interaction.

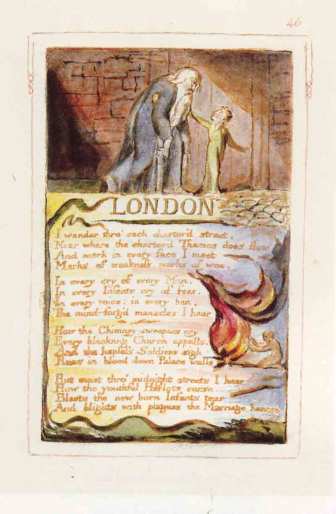

I don’t think this is right. There is no writing that does not involve consciousness of audience, so we’ll leave that aside. The difference here is not simply speed. It’s that the entire process of the blogosphere is wired differently, with trackbacks and comments and aggregation, etc. One PSU person commented on the forum that all this talk of trackbacks and so forth sounded like mere logistics. I understand why that person might think so, but that’s precisely the opposite of the point (and I certainly need to do a better job of explaining why). In New Media, webby logistics shape and extend content, and thus change the conditions and possibilities of content, and thus begin to alter our notions of what counts as content and how we will create it. The medium is the message. A link is not just a technical contrivance. It represents something new in terms of implicit and powerful citation/association, something that’s as much a game-changer as the alphabet. If trackbacks are logistics, so is language itself. Similarly, blogs furnish a very different model of peer review, what Shirky terms publish-then-filter, instead of the traditional filter-then-publish. When one begins to understand those possibilities, to assemble a network of filters and amplifiers (Udell) that make that system sing, one finds a huge and powerful set of differences between blogging and sending an article to a professional journal that goes well beyond speed. No peer review. Built in comment affordances. Permalinks. Trackbacks. Feeds. Aggregations. Embedded images and video and audio. One can commit art in a blog, and should!

The more I’ve experimented with this seminar, the more it has been growing on me that blogging represents something fundamental that needs to be more widely and deeply understood. I actually spent a little more time on that with my group at Baylor this year, and it seems to have paid off very well. So this may be another area to push forward. Believe me, it’s radical!

Are you saying that more creatively social approaches are unnecessary in this seminar?

Not at all. There’s room for much growth and improvement here. This first iteration of the networked seminar makes that clear to me. And of course that’s one reason the maiden voyage is so important. I agree we need to work the social aspect much more vigorously—but I still maintain blogging will be a key part of the platform we build.

But is blogging really social and interactive? Can’t we explore more interactive tools?

We should always explore, certainly. No problem there. But again, I want to unpack the assumptions a bit. Blogging can be highly interactive and social. It’s built to be that way. It certainly has been interactive and social in my experience, profoundly so. But it does demand commitment far beyond Foursquare check-ins (not that there’s anything wrong with that). It demands deep intellectual engagement. And I believe that only deep intellectual engagement can move us in a positive direction, away from what is so often the witless or flogged technology practices we’ve seen in higher ed.

And here’s another thing I think about: why is “deep intellectual engagement” of this kind something so difficult to get going in higher ed? Does anyone see anything wrong with this picture? 🙂 Where’s our curiosity and spirit of adventure? We ask so much of our students, but it’s hard for us to write two or three paragraphs about something *we’re* learning, to be that open and curious and wondering and vulnerable. See, that’s the radical idea … that we should learn in front of each other.

Well, what if instead of reading Ted Nelson, we explore Xanadu virtually, for instance.

GC: In *addition to*, sure. The Baylor facilitators that day actually played for us a video of Nelson explaining Xanadu, and doing that was both stimulating and helpful. I feel strongly that seminarians should bring some kind of interesting new media into every session. We’ve certainly tried to do that at Baylor. But why *instead of*? In my view, we could explore Xanadu all day, but unless we’ve read the impassioned and provocative excerpts from Nelson’s manifesto, the experience will be superficial, weightless—just another interesting tech demo. We’ve had enough of these, and they just don’t change anything.

And for most of the folks who blogged about it, Nelson’s essay was easy to read–even fun. Folks enjoyed his spicy rhetoric. I’m not sure the problem is spice. But the readings need to be framed and experienced as vital, deep explorations of essential challenging ideas. I think that’s not only possible, but necessary. The book and essays are the platform. Build the social stuff on and through and around it, yes, but at the end of the day, if we want to know where Nelson is coming from, his crazy multimodal manifesto is the foundation. And it can be fun—and is for many people, potentially for everyone if they just relax and go with it!

Shouldn’t we be modeling the kind of pedagogical innovation we want to bring to our undergraduates? Are reading and conversation really innovation in terms of a course of study?

GC: This isn’t a “course” in that sense—at least, as I’m struggling to articulate it. It’s more like a reading group on steroids, a deep conversation, a think tank, a set of community activists in fellowship. No doubt we can mix the experience up more to help the readings come alive for folks who are struggling to get their imaginations awake in that medium. But the idea is not to leave the medium of the essays behind—it’s to *augment* them, and by augmenting them, to awaken our digital imaginations.

I’m confident that NMFS is not the only way to do it. But I’m also confident that it’s never really been tried like this. And I’ve seen such rich results from my undergrads and now from my colleagues at Baylor that I think the thing to tweak is not the basic philosophy of the seminar, but the ways in which we can mindfully work together to make that experience as rich as possible. Remember that it was an *undergraduate* class that led to the NMFS. In many respects, one of my primary goals with this experiment is to model the idea of the *seminar* in a purer and less encumbered way than one typically finds it in higher ed. My experience has been that a seminar like this is pretty radical for the undergrads too—we talk about this with some frequency.

For me at this point, the problem is not the idea of a seminar, it’s that the idea of a seminar has become corroded and compromised by all the clanking of the industrialized model of schooling. A real seminar, where we’re all learning together, where we’re all bootstrapping and augmenting ourselves into a fuller level of understanding, is highly innovative in a world of grades, semesters, products, GPAs, credit hours, etc. Or so it seems to me!

I guess we’re learning as we go, as guinea pigs for each other. We’ll press onward through the fog.

Part of any learning experience is watching the fog lift. Some weeks are foggier than others. I felt foggy last week. Not so much this week. Here’s one huge reason why: http://homepages.baylor.edu/lance_grigsby/what-we-behold-becomes-us-too/. I really do think the blogging is key. A good motherblog is key. Recirculating/aggregating/displaying comments. Being explicit about what a blog is and how it works and what it can be and can mean. It’s the whole package. I agree wholeheartedly that we need to be more explicit and have deeper conversations about how all this augmenting is designed. Maybe the local leaders/facilitators need to be in intensive conversation for two or three days before the next iteration. In fact, I think that’s a great idea (and I’m very grateful to the colleague who suggested it). We really do need to understand the platform at the outset, so we can share it with confidence with each of the local groups. I think about the Center for Digital Storytelling in this regard—they’ve got this “train the trainers” thing down cold.

And hey, if folks want to do their own thing, that’s fine—that’s what was happening before any of this started. But I have to say that I am firm in my conviction that we need to be in *idea space* (Kay) and the way to get there most deeply is by reading and talking about and blogging about these essays, augmented by all the new media wonderfulness we can muster. Without that depth, we just won’t get the traction we need. Without that traction, we can’t move toward the change or reformation we desire.

It’s been quite a week since

It’s been quite a week since