No, it wasn’t a computer, though it was built on the principle of programmed learning. It was a World Book Cyclo-Teacher. The kit came with big printed instruction-question-answer wheels that fit onto the machine’s hub, as well as smaller blank white-paper wheels that fit atop the larger wheels. As I recall, once the big wheel and smaller wheel were in place, you closed the Cyclo-Teacher lid, took up your pencil, and began the circular journey. Some windows gave you information, some proposed a question, and there was a space for you to write your answer (the questions were multiple-choice, as I recall). After you wrote your answer in the midst of this exciting multi-screen display (I confess: it did look kind of cool to me at that time), you pushed the little plastic lever in the midst of the machine to the right, thus advancing both wheels to reveal the correct answer, new bits of information, and a new question.

I may have some of those details wrong, but you get the idea. Step-by-step instructions, chunked content, all clear as can be, with frequent instant feedback. Not adaptive, to be sure, but not so far from the idea of clear instruction, clearly articulated learning outcomes, and rock-solid assessment.

From this Cyclo-Teacher I learned the rules of chess, but I did not learn how to play chess. I did not learn to play chess until I began to play chess. This may seem like a subtle distinction. To me, it made–and makes–all the difference in the world.

Real school must support both the rules and the playing. And the greatest of these is the playing. One can learn rules by trial-and-error within the playing, if one’s opponent knows the rules. But that’s very slow. Much faster to use some kind of instruction–faster, but not better, not unless learning the rules is always in the context of the playing. That observation, I take it, is at the heart of Lockhart’s Lament, and at the heart of Bret Victor’s “Kill Math” as well.

The playing not only manifests but encourages and empowers understanding, for it is the mode in which knowledge becomes not simply procedural but generalizable. Jerome Bruner puts it this way:

The child first learns the rudiments of achieving his intentions and reaching his goals. En route he acquires and stores information relevant to his purposes. In time there is a puzzling process by which such purposefully organized knowledge is converted into a more generalized form so that it can be used for many ends. It then becomes “knowledge” in the most general sense–transcending functional fixedness and egocentric limitations.

A puzzling process indeed, but one we cannot ever overlook, for this puzzling process is also the mode in which meaning emerges, since meaning emerges not from procedure, but from relationship (also a puzzling idea, but irresistible). My complaint about the culture of “learning objectives” and “learning outcomes” is that it seems to me very often to be a sophisticated and indeed frightening recipe for “functional fixedness.”

But didn’t I have to know the rules of chess to be able to play chess? Of course. And the Cyclo-Teacher worked for me because I already wanted to learn to play chess, and because there was no context to confuse me about what I was doing. No classroom, curriculum, well-meaning instructor, grading scale, tuition, degree, or cultural capital. I was using a teaching machine as an elaborate set of flash cards so I could commit some procedures to memory. I knew that’s what was happening. I didn’t think I was playing chess, or watching someone play chess, or learning about playing chess.

All analogies will break down, and this one will too. Before it snaps, though, I’ll say again what I tried to say here: confusing the rules with the playing is a big mistake, and it’s a mistake that seems to me to be propagating throughout school because of a narrow emphasis on the structure of instruction and a desire for rapid, consistent, scalable forms of assessment. The result is all too often a paradigm (even a recipe) of instruction purpose-built to fit into rapid, consistent, scalable forms of assessment. My belief does not necessarily contradict or even oppose a belief in the value of learning times-tables or any other procedural knowledge. My aim is to argue against models of learning that implicitly or explicitly assume that understanding proceeds in a linear or predictable fashion from procedures, or that we can afford to relax about “understanding” because we all believe in it while at the same time we say that it’s “mushy” and therefore able to be omitted from our discussions of particular modes of instruction. My claim here is that any time we omit “understanding” from our discussion of learning or teaching, we do so at our extreme peril. It’s too easy to get into the habit of such omissions.

In Leadership Can Be Taught: A Bold Approach For A Complex World, Sharon Parks makes an exceptionally important observation:

In all educational experiences, people to one degree or another model themselves after the teacher, learning things that are not in the explicit content of what is being said or read, but that are implicit in the way the teacher goes about teaching. It is easy for teachers to underestimate how much is taught about ‘how to be’ that goes unexamined. Students unconsciously drink in, for example, the way a teacher models the resolution of conflicts in class, solves problems, handles the introduction of deviant, innovative, troubling, or confusing points of view, and exercises authority. Lessons about professionalism and expertise are absorbed and reinforced class after class–year after year.

Parks’ words remind me why I find it so painful to hear about “delivering” the “content” of a course. Every choice the teacher makes, from the way the syllabus is written to the way the requirements are described to the way grading is explained to the way she or he demonstrates and confronts her or his own uncertainty, curiosity, interest, awe, and wonder to the students, models something about what it means to be human, what it means to learn. Every choice a teacher makes elicits, and answers or evades, the biggest question of all: “so what? Why does this matter?”

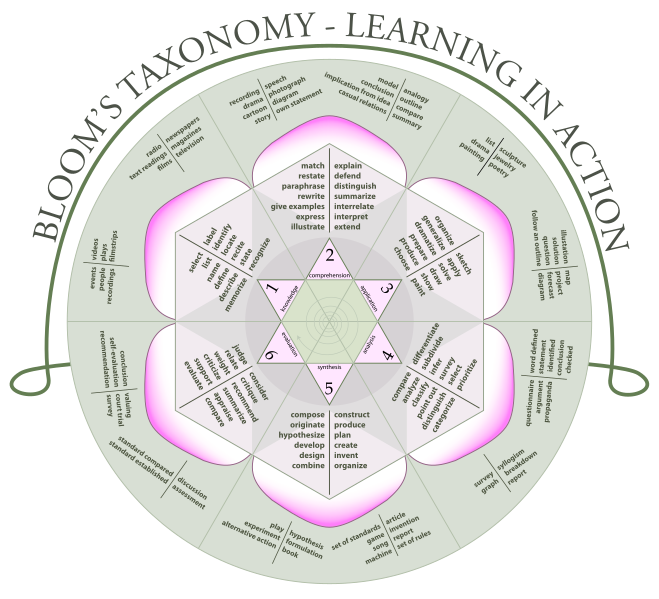

My experience also leads me to conclude that the culture of “learning outcomes” that anticipate or imply linear paths from LOTS to HOTS (lower-order thinking skills to higher-order thinking skills–yes, those are the acronyms) reveals a culture that also believes in the fool-proof curriculum, the sequence that will lead to learning as repeatable, predictable, and reliable as the trajectory of a ball dropped from the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Thus curriculum becomes a technique rather than an experience (or rather than a good, strengthening experience of meaning-making). Robert Evans tells a tale of his own mistake in this regard, a tale that certainly rings true in my own experience of schooling:

In 1968 I joined a team of teachers that sought to develop a high school English curriculum that would be both highly relevant for students and “teacherproof,” with content so engaging that it would make students want to learn and lesson plans so clear that no teacher, however dull or incompetent, could fail to conduct an interesting class. As comparatively simple as our reform was, it proved futile…. One of the central lessons we think we have learned about previous rounds of innovation is that they failed because they didn’t get at fundamental, underlying, systemic features of school life: they didn’t change the behaviors, norms, and beliefs of practitioners. Consequently, these reforms ended up being grafted onto existing practices, and they were greatly modified, if not fully overcome, by those practices. Dull and incompetent teachers taught the new content dully and incompetently.

The flaw here, as some see it, is that most of these projects aimed at first-order change rather than at second-order change. First-order changes try to improve the efficiency of effectiveness of what we are already doing…. They do not significantly alter the basic features of the school or the way its members perform their roles. Second-order changes are systemic in nature and aim to modify the very way an organization is putt together, altering its assumptions, goals, structures, roles, and norms…. They require people to not just do old things slightly differently but also to change their beliefs and perceptions.

Heifetz and Linsky reach similar conclusions about failure to change in their classic study Leadership on the Line: Staying Alive Through The Dangers Of Leading, They call “first-order change” technical change, distinguishing it from adaptive change, which corresponds to Evans’ “second-order change.” (It’s interesting to consider learning as a special case of leadership, or vice-versa, as becomes clear in Sharon Parks’ analysis of Heifetz’ approach in her book Leadership Can Be Taught.) In both analyses, the greatest risk of highly damaging “functional fixedness” comes when we shrink from the challenge of second-order or adaptive change by simply falling into denial and calling “second-order change” what is really only first-order change in disguise. Note that the “functional fixedness,” the inability to generalize, occurs at all levels if we do this. The sad fact is that teachers will be as damaged by functional fixedness as the students they teach. That’s the awful, malignant self-feeding nature of this beast. This is part of what I was trying to get at in my “Personal Cyberinfrastructure” piece as well as its predecessor, “No Digital Facelifts.”

How shall we assess our students’ learning if the outcome we seek is stronger and more effective modes of meaning-making from our fellow human beings, especially those who trust us to shape their brain’s capacity for shaping itself over a lifetime? Those who trust us not only to awaken them to a high-def world that surrounds them, but to awaken (or at least not to dull) their appetite to build worlds and not simply to endure them? Now that’s a learning outcome. It’s a complex ambition, to be sure, but I believe we must hold it in mind at all times and communicate it in everything we write, speak, or build in support of learning. This is not the 30,000 foot level. It is the ground upon which we build. Yes, it is also often a ground made of paradoxes:

Does this mean that there is no use taking biology at Harvard and Shreveport High? No, but it means that the student should know what a fight he has on his hands to rescue the specimen from the educational package. The educator is only partly to blame. For there is nothing the educator can do to provide this need of the student. Everything the educator does only succeeds in becoming, for the student, part of the educational package. The highest role of the educator is the maieutic role of Socrates: to help the student come to himself not as a consumer of experience but as a sovereign individual. (Walker Percy, “The Loss of the Creature”)

I’m confident Percy’s absolutes are designed to make us think, but for me and perhaps for Percy as well (I have a sneaky suspicion about this), “nothing” is too strong, as is “everything.” After all, we have Percy’s essay, itself a meta-maieutic experience, or perhaps a commentary that helps one think more intensely and ably about the highest role of the educator–and that’s a long way from nothing, at least for this student.

As Jerome Bruner writes in a slightly different context, “It is too broad a task I have set for myself, but unavoidably so, for the question before us suffers distortion if its perspective is reduced. Better to risk the dangers of a rough sketch.”

I understand and support the need for maps, for rules, for procedures, for precision. At the same time, I believe these are means to an end, and the desire for them springs most authentically when the teacher keeps the end in sight of both the students and him or herself. Keeps the end in sight, and understands that it is the end, in its other role as a beginning, that brings the procedures, maps, rules, and precision into being.