How could anyone resist a session with this title–and this layout for the schedule display?

So I went to Bret Victor’s session, arriving about fifteen minutes after he’d begun. There was an animated fish on the screen, and a worm on a hook, and sometimes bubbles, and sometimes a little wheel (that I later learned was a timing element). Bret was demoing the most recent iteration of his Dynamic Pictures research. The idea, as I understand it (and my understanding of it is just beginning, so this is all memory, exploration, interpolation, and probably full of mistakes and gross oversimplifications), is that math is not only about language, as in an abstract set of symbols, either mathematical symbols or programming code. Instead, math is also about geometry, visual representation that can move and be acted upon directly through a UI that nevertheless asks the user to think abstractly about what’s happening “concretely” in the visual representation one is manipulating.

Bret’s project is to use the computer to allow for new methods of reasoning–or perhaps not “new” so much as “newly applied.” We now have the tools to allow us to think, to reason, in differently mediated ways. Why not use them to do so?

The session was mesmerizing and so … different … that I had a very strange sensation as I tried to take it in. I felt at the very edge of my zone of promixal development. That is, I could understand what Bret was saying as he was saying it, but that cognitive bubble was very small, so small that I found myself with no extra resources for deep metacognition. At the same time, I also felt as if I had had this experience already at various times in my life: when I fingerpainting in kindergarten, when I got my Radio Shack 50-in-1 electronics kit for Christmas, when I got my first stereo and began to understand what “soundstages” were in audio reproduction.

Picture from an Ebay seller. Mine is in better shape (and in Texas right now).

What all of these experiencs shared was a strange, almost surreal link between the world of objects and the world of thought, as if a sufficiently intense thought could create something material, or as if a sufficiently intriguing, provocative, or alluring material object could somehow emit thoughts as if those thoughts were embedded within it. Longtime readers will recognize that the “meaning” and “doing” modalities here are part of my obsession with poetry, with the myth of Orpheus, with John Donne and T. S. Eliot, with computers and stereos and electronics generally. Bret is an obsessive’s obsessive whose mental landscape must be a mashup of Magritte, Tufte, Mike Oldfield, Cervantes, Alan Turing, and Ada Lovelace. To name only a few.

Doug Engelbart came strongly to mind during Bret’s demo, as his ideas of hypersymbolic communication and the next stage of human evolution seem eerily realized and advanced by Bret’s work.

If I recall correctly, Bret himself cited Seymour Papert’s work with LOGO and the programmable turtles as an influence. The interesting difference here is that Bret takes Papert’s turtles and re-abstracts them into the realm of visual representation, with the twist that dynamic visual representation then becomes the origin point, not the result, of programming. It’s as if one programmed the computer by moving the turtle–but the motion is realized with the precision and yet also the familiarity (tactile, motor, cognitive) of a simple drawing. A virtual turtle that moves the mind that imagines it.

Bret’s website–actually, I’d call it his cognitive exoskeleton–is worrydream.com. It’s actually (online) cognitive exoskeleton 3.0. His previous websites, linked on the new one, also repay close investigation. The biographical sections are very interesting, as the representation of self in language, to my mind (heh), is analogous to what Bret is doing with his dynamic pictures. The precise modes of “interaction” and dynamism that linguistic self-representation enacts (particularly in poetry) are extraordinarily complex, of course, and more than I can get into here. But I wanted to register the resemblance.

To bring in one more of my favorites, I don’t believe I’ve ever seen a more convincing elaboration or illumination of Alan Kay’s aphorism that “the computer is an instrument whose music is ideas.” (I just learned that Alan Kay knows Bret’s work–of course he must–these circles are unbroken–lovely to see this.)

The climax of the session for me was “part three,” in which Bret performed a short video uniting myth, the creation of life, the rise of cities, space flight, and a panoply of human voices that, unlike the ones Prufrock hears, wake us and we breathe…. You had to be there. You’d have heard the whoop than rang through the room as we responded to what we’d just experienced.

Tweets for Bret Victor’s demo at FOO Camp 2012

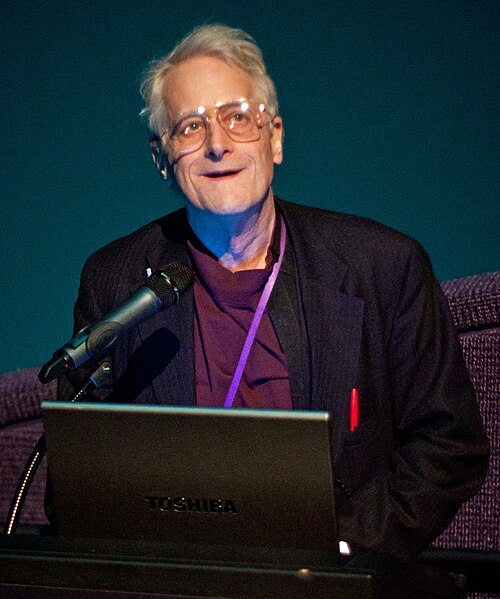

I sensed it’d be something special, and I did make an iPhone video that works for me as a souvenir. I don’t know how intelligible it would be for others. Perhaps all you need to see are the gestures, the timing, the slight swaying-to-the-beat. Here’s one frame from the video, toward the end:

See the way that fellow is leaning forward? Take that as a representation of what I think we were all feeling at that moment.

Bret’s Twitter page has a one sentence profile: “The Prerequisite Is Hope.” Bret’s logo is a windmill. As I write of this remarkable session, I find myself wishing I could spend a semester (or more) of advanced study as a cognitive apprentice to this young man. Anyone who gives Papert’s The Children’s Machine seven stars on a five-star scale is someone I would gladly know better. Perhaps our paths will cross again. The trick for me will be to retain the enthusiastic naivete that would keep me hopeful, instead of the all-too-easy sinking feeling that would make my naivete cower in shame. That’s a roundabout way of saying that if I’d known as much about Bret before FOO Camp as I’ve been learning since, I’d have been too self-conscious to rush up to him and say hello the way I did the day before. And that would have been a great shame and a greatly wasted opportunity.

EPILOGUE:

After Bret’s session, I wandered to the big tent for the closing session. I was a bit disappointed. Tim and Sara spoke briefly. Tim said he thought the Camp had gone very well indeed, and that it was a fitting 10th-anniversary iteration of the grand idea. Sara thanked all who’d made it possible. We yelled out our thanks in return. There was applause. And that was it. I’m not sure what kind of closure I expected or wanted. I know everyone was worn out. But I wanted more reflection from the leaders, I guess, more of a sense of their hopes and dreams. Sometimes one wants a sage on a stage–the key word here being sage. I have no problem with the sage on the stage when I feel there is wisdom to be gained, as I did here.

So I walked around for a bit afterward, looking at the now-empty spaces where just a few moments before there’d been such a buzz of activity and conversation. I like walking through such spaces and hearing the mental echoes of the presences I’d experienced there. I learned those pleasures when I did theatre in high school and college, and found I enjoyed walking around the set after everyone had gone home, or even after the play had closed. Something about moments and people and the places we inhabit, something about the relation of mental space and emotional space and physical space.

As I kept on wandering, I found myself heading upstairs in Building B to look at the Make Lab, one place I hadn’t been during the weekend. There I found a set of folks still busily engaged in various activities, as if the weekend were still going strong.

In this corner of the O’Reilly multiverse, the Camp hadn’t ended after all. I now understood the sign I’d seen on the Conference Schedule wall earlier in the day:

I have a sneaky suspicion Bret Victor made this sign.

Unparadoxically (guess I watched my steps well), it turned out that it wasn’t too late to get a 3D printout of my head. A “bust of Gardo.” I got in line, got scanned, and got my printout in the queue. “Come back in about an hour and a half,” I was told. So I did, and you can see the results here.

Many thanks to Sabrina Merlo for that ultracool photo. Special thanks to Eric Chu for his patient, welcoming work on the scanning and printing, and on answering my many questions about the process, all long after folks were vacating the campus. Really, everyone at Make Lab was amazing. I felt a depth of connection there that took my breath away and helped me feel less like an outsider and more like a fellow geek. It was a superb ending to the FOO Camp experience, one in which I had many conflicting emotions, chief among them my great desire to make the most of the time I was there by contributing to it in some meaningful way.

I found that “making the most” was difficult for me this go ’round. In other experiences like this, most notably the Governor’s School in Virginia and the Frye Leadership Conference, I’ve found the “come on in” portal sooner, or more securely. I didn’t really find it here until I found the Make Lab on the final afternoon. Having found it there, I could see the places the portal might have been flickering earlier in the weekend–or even places I might have walked through that “come on in” portal without knowing it. Hard to say.

But as you can tell from this series of blog posts, my first blogging in (I regret to say) over three months, the experience made a huge impression on me. Looking back a week later, I can see that these posts came out of a strong sense that if I hadn’t found a way, I had to make one. Just like the tagline says. So these posts are my portal, and for what they’re worth, my contribution.

One last thought. Before I got my invitation to FOO Camp, I may have heard of the gathering, but I had no idea, really, what it was, or why it was, or who had been. During the Camp, several tweets appeared in the stream from folks who weren’t there. Some were angry, some were rather snarky and resentful. For some reason it always surprises me to see such things, which is very strange, as such responses are utterly predictable and have a long history in all things human. While it wasn’t fun to hear virtual raspberries, especially when I felt very much the outlier and was trying hard to make sense of it all myself, I am gradually becoming more aware of FOO Camp’s place in the larger hacker/maker/thinker culture in which it exists. All very complicated, to be sure, but in some ways I also feel as if I’ve been here before: the always-difficult balance between community and exclusion, between the drive for excellence and the gradual narrowing of one’s criteria for excellence.

I was bemused (not amused–there’s a difference–see definition one) to see this tweet shortly after the Camp ended:

Required reading for all #foocamp-ers -> The Inner Ring by C. S. Lewis lewissociety.org/innerring.php

A salutary caution indeed. Yet the care the FOO Camp leaders take to refresh the group each summer by making fully half of the crowd new attendees suggests the leaders are mindful of these dangers as well. And there are outliers–more of us than I might have imagined–who have little or nothing to do with Silicon Valley or hacking or web development. Still: point taken. And I did reread the essay. At one point Lewis writes, “Until you conquer the fear of being an outsider, an outsider you will remain.” Interesting that his caution can apply equally to people who believe themselves “in” and to people who believe themselves “out.” I guess it comes down to motive, to “desire” (Lewis’s word), to the why of one’s participation or ambition. But here I feel a Milton essay coming on (all these topics are covered in his work, to stunning effect).

So that’s it for now. To all at FOO Camp, but especially to Tim O’Reilly and Sara Winge for leading the Camp, and to the person or persons (you know who you are) who suggested I be invited, my thanks. I’ll be thinking about this experience, and working through it, for a very long time to come.

Thanks also to Virginia Tech and the good folks in the Division of Learning Technologies for supporting my travel and participation.

A dream we dreamed one afternoon long ago.

Good evening.

Good evening.