Steve Greenlaw over at Pedablogy said very nice things about the preceding post, and I’m grateful. Moreover, I want to show my gratitude. But Steve asks for practical suggestions. You’d think we’d just met. Have I ever given him practical suggestions? Well, okay, perhaps once or twice. I do try. Actually, I thought I had put some practical suggestions into the preceding post. Yet I suppose it all came out the way it does most of the time. What he gets from me is what everyone gets: dreams and myths and song lyrics and movie quotations and cryptic mutterings about this and that delivered with mournful looks or hand-waving manic excitement. Steve’s patient with my cryptic mutterings. I do try to save some of my best ones for him.

So here are some mythy dreamy non-practical practical suggestions, by semi-request, in honor of Pedablogy’s fifth birthday (back in May; I’m late).

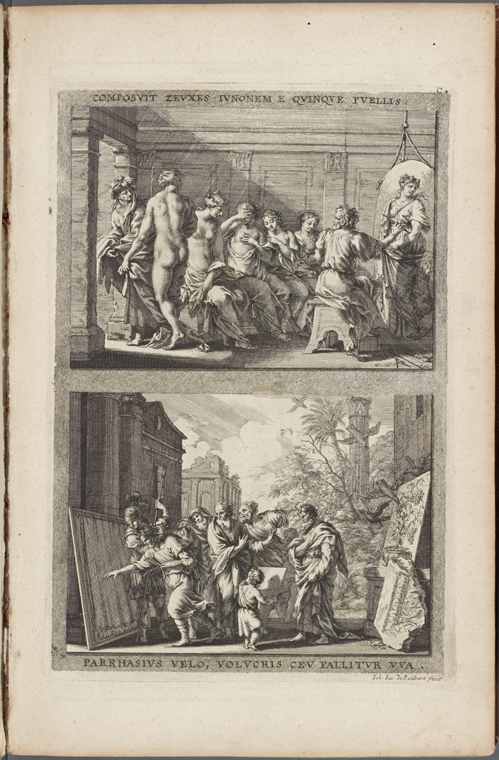

I’m fascinated by the tale Pliny the Elder tells of a contest between two Greek painters, Zeuxis and Parrhasios.[i] (I’m using it right now in a Milton article I’m trying to write.) Which of these painters could craft the most compelling representation? The word “representation” is important here. These paintings were made to imitate visible reality, and the extent to which they tricked the eye (thus “trompe l’oeil”) would determine their success. With a century and a half of technological image capture behind us, we may ourselves judge such a contest as aesthetically unsophisticated, yet the story as Pliny tells it has deep resonance for all lovers of poetry and symbolism. I think it has deep implications for teachers and students as well. What motivates interest? What representations of knowledge, in the moment of learning facilitated by a teacher, inspire curiosity?

Zeuxis shows his painting first. He removes the cover from the canvas, to reveal a painting of a bunch of grapes. The grapes’ verisimilitude delights the crowd, and the audience responds with praise. Yet an even more persuasive endorsement is near, as several birds swoop down to the painting to peck at the grapes, so complete is the representation, so powerful is the illusion. One might at that point judge the contest decided. If the natural world itself is fooled by a representation is such a direct way, uncolored by subjectivity, the representation is essentially perfect. I’d link this perfect representation to an utterly clear, well-organized set of descriptive information presented to students as if teacher, classroom, and student were all blank canvases ready to receive the crystalline perfection of the precise and authoritative exposition of the subject matter. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that, in the Seinfeldian sense.)

But the contest has another layer of perfection to be revealed. I’ll quote directly from the translated text of Pliny’s Natural History:

Parrhasios then displayed a picture of a linen curtain, realistic to such a degree that Zeuxis, elated by the verdict of the birds, cried out that now at last his rival must draw the curtain and show his picture. On discovering his mistake he surrendered the prize to Parrhasios, admitting candidly that he had deceived the birds, while Parrhasios had deluded [Zeuxis] himself, a painter.

That moment is for me a parable of engagement, of the kind of hungry interest that can drive a learner both faster and deeper than anyone might imagine. Zeuxis’ cry begins the experience. In some senses it defines the experience. It’s a complex moment: something great is at stake for him, and the event has already brought him a considerable triumph. We can think about the ways in which one can construct the drama of the learning moment, and how one can bring some experience of elation to any learner at any level. The deepest bit for me, though, is that urge to lift the veil. The urge has little to do with crystalline clarity of exposition. And it has everything to do with interest. I felt that urge when I went to college. I was a first-generation college student, working class, ready to find a more comprehensive sense of the mystery and complexity of the world and learn to articulate it for myself. Many teachers who work with similar students report they are “hungry” for an education. Encountering a student with that hunger, and helping that student find the food that will both satisfy and increase that hunger, is one of the great and humbling rewards of being a teacher.

But what to do with the students who, like the one Steve describes in this post, are simply not hungry, who announce (with pride? defiance? boredom?) that they have no interest in the subject being taught? And what of those students who are hungry, but who have had their interest quashed by teachers who may well be interested in their own interest but have not learned to be interested in their students’ interest, to be fascinated by the growing fascination with areas that may be “old hat” for the teacher but feel like radical innovation, even revelation to the student?

I suppose that’s my cue for practical suggestions. I think these work for all three types of students I’ve described above. They’re all about making a veil–really, a kind of meta-representation–that elicits a cry for revelation.

1. Practice being visibly interested in your students’ interest. (Go meta; Google recursion (H.T. to Tim Logan)). Watch them like a hawk for any flicker of curiosity, confusion, or awe. Don’t pounce, but do attend, and let them know that you find their interest fascinating, or at least potentially fascinating. This requires top-notch listening skills, patience with digression, and the steely discipline not to look down, away, or at your watch/cell phone/class clock/notes whatever. There has to be a rhythm here, of course. If you’re hanging on their every gesture, students will a) not believe it and b) begin to find you rather creepy. You also don’t want to pander to them by suggesting everything they say is right, deep, astonishing, etc. What I’m suggesting here isn’t really about praise, however. It’s more about finding their interest interesting, and letting them know that. You can tell them when they’re wrong, misguided, etc. What’s not good is to miss the signs of interest, or to ask merely for repeated information (though that has its place, a steady diet is pretty deadening), or employ a kind of mock-interest merely as a way to use their contributions to take you to the next step in your own well-laid instructional plan. The latter strategy is perilously easy to spot. Next thing you know, the students will be feigning interest right back at you, and then the jig is up for everyone.

2. If you can connect your interest in their interest to your interest in the subject matter, you’re actually demonstrating a vivid human and social context for the life of the mind. That context is, I believe, one of the primary reasons for school in the first place–not that you’d know it from some of the last century’s industrial strategies, some of which people are trying even now to sustain in this century as well.

3. Include robust portions of the conjectures and dilemmas that drive your particular areas of intellectual concern and the methodologies that drive your inquiries into those areas (in other words, your discipline). Searching through my blog archives, I see that I’ve invoked Jerome Bruner’s idea of “conjectures and dilemmas” many times without actually quoting the wonderful story with which he illustrates his concept. I will now correct that oversight! A long quotation follows. Trust me: it’s worth it.

There are several quite straightforward ways of stimulating problem solving. One is to train teachers to want it, and that will come in time. But teachers can be encouraged to like it, interestingly enough, by providing them and their children with materials and lessons that permit legitimate problem solving and permit the teacher to recognize it. For exercises with such materials create an atmosphere by treating things as instances of what might have occurred rather than simply as what did occur. Let me illustrate by a concrete instance. A fifth grade class was working on the organization of a baboon troop–on this particular day, specifically on how they might protect against predators. They saw a brief sequence of film in which six or seven adult males go forward to intimidate and hold off three cheetahs. The teacher asked what the baboons had done to keep the cheetahs off, and there ensued a lively discussion of how the dominant adult males, by showing their formidable mouthful of teeth and making threatening gestures, had turned the trick. A boy raised a tentative hand and asked whether cheetahs always attacked together. Yes, though a single cheetah sometimes followed behind a moving troop and picked off an older, weakened straggler or an unwary, straying juvenile. “Well, what if there were four cheetahs and two of them attacked from behind and two from in front. What would the baboons do then? The question could have been answered empirically and the inquiry ended. Cheetahs don’t attack that way, and so we don’t know what baboons might do. Fortunately, it was not. For the question opens up the deep issues of what might be and why it isn’t. Is there a necessary relation between predators and prey that share a common ecological niche? Must their encounters have a “sporting chance” outcome? It is such conjecture, in this case quite unanswerable, that produces rational, self-consciously problem-finding behavior so crucial to the growth of intellectual power. Given the materials, given some background and encouragement, teachers like it as much as the students.

To isolate the major difficulty, then, I would say that while a body of knowledge is given life and direction by the conjectures and dilemmas that brought it into being and sustained its growth, pupils who are being taught often do not have a corresponding sense of conjecture and dilemma. The task of a currculum maker and teacher is to provide exercises and occasions for its nurturing. If one only thinks of materials and content, one can all too easily overlook the problem.

Quoted from Jerome Bruner, Toward A Theory of Instruction (Harvard Univ. Press, 1966), 158-159.

“Life and direction” are good eye-catchers–and good I-catchers, too. A caution: one should not confuse the teaching of conjectures and dilemmas with “teaching the conflicts” (as Gerald Graff urged us to do at the zenith of the era of high-theory epistemological panic), which in my view has real but highly limited value. Demonstrating that people have different opinions. judgments, points of view, foundational assumptions, etc. may take some very sheltered students by surprise, which is its real value: it inculcates a certain kind of tough-mindedness. But it’s not a conjecture, nor is it a dilemma. A conjecture is what Bruner calls an “invented” answer, not a “found answer,” and of course original thought doesn’t not proceed by merely looking up answers that are already there. And a dilemma is “a problem offering at least two solutions or possibilities, of which none is practically acceptable” (Wikipedia). In my experience, “teaching the conflicts” never gets to the conjectures that inevitably emerge from incomplete data or the dilemmas that emerge when one takes conjecture and incomplete data and nonetheless feels compelled to act or reason in one way or another.

4. Everett Rogers argues that observability is a major factor in the diffusion of innovation. I believe that this argument works for interest as well. Interest spreads when it’s observable. How can students observe each other’s interest? Well, one way is to have everyone sit in a circle, where a circle is defined as everyone’s being able to see everyone else. (Many “circles” fail this test, in my experience. I always insist on it, and I clown and cajole until I get it.) Another way is to play a game, one in which the players’ interest and engagement are readily visible and drive the entire experience upward in terms of its intensity and fascination (my colleague Blaine McCormick does this with a game in his intro marketing class). Yet another way is to create a visualization of individual expressions of interest, both in and out of the class meeting, and make that visualization available to the class and (this is important) to the world as well. We teachers feel pretty good when students say they’re interested in the classes we teach, but what we really want, I think, is for students to be interested in what the class is about, what it represents in the life of inquiring minds around the world, what this one course and one semester stand for more largely and importantly. For that to happen, there must be ample provision for displaying student reflection (e.g. blogs), resource collection (e.g. Delicious, Flickr), and in-class thinking (e.g. Twitter) to the world. It’s one thing to tell students that the local class meeting has lifelong, global, even eternal significance. It’s another thing altogether to connect to the global network and raise the possibility of contact and interaction with that field of larger significance (i.e., civilization). Who will read my blog? Is it possible that nearly anyone in the world might? Whether or not a miracle comment from an expert, an alum, a parent, another classmate ever emerges, the tantalizing possibility of that contact lends urgency and a bracing sense of expectation to the work and its aggregation. Ditto for Delicious: students see on the motherblog, or in their reader, or wherever, that their classmates are thinking about the class when the class isn’t meeting. One might imagine such a thing happening, but something as simple as an RSS feed in a sidebar will demonstrate that fact–and the observability of that demonstration of ongoing interest will drive more interest. At every juncture, then, we must think of ways not only to elicit and nurture interest, but to make the aggregated display of the students’ interest into an object of interest itself, thus perpetuating a most virtuous cycle. We will find ways to make interest go viral–and “we” in this case primarily means “the students themselves”–but only if their individual work, as appropriate, is visible to the entire class and, as appropriate (which is more often than not), to the world.

I never intend to write these elephantine posts. But having “wreathed my lithe proboscis” yet again, with my Jumbo apologies any my hopes that something in all of the above is useful, perhaps even practical, I take my leave with a quotation from Steve’s very first blog post at Pedablogy–what I’d call the most practical suggestion of all:

I’m writing this blog primarily for myself. For years I’ve had stray thoughts that I have wanted to think through, but ended up slipping away. I’ve decided to let this blog be the place for me to think through those thoughts.

Rock on, brother, and amen.

[i] My source for this episode from Pliny’s Natural History is The Elder Pliny’s Chapters on the History of Art, translated by K. Jex-Blake (Chicago: Ares Publishers Inc., 1977), 109-111.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Practical Suggestions « Gardner Writes -- Topsy.com

I feel like we are too much in love with our perfect curtains

and representations of grapes, and perhaps do not appreciate the

wonder of the real birds and their hunger for something which

is part of the ecological fabric. I feel like there is something sensible

in the cultures which are cautious to avoid valuing our own representations of natural beauty over the web of life we depend on.

I feel we are systemically reliant on our representations over

direct observation of the actual and that this is a cost of working at the kinds of scales which we believe are efficient and profitable.

And yet I am painting frogs to send a picture to the council of the animals which are being wiped out by the graders sweeping the creek beds for the new housing development. I guess it is tricky to effect change without representation when that is all that is systemically recognisable.

All the best from the south.

mm probably pesky and tangential, hopefully not polarised/ing